No indignity is spared in this NTGent production of Platonov, directed by the Belgian theatre and film director Luk Perceval. Platonov (its English-given title) is a 105-minute adaptation of an unwieldy early play by Anton Chekhov, written by the Russian between the ages of 18 and 21. Completed in 1878 and with a playtime of around 6 hours, Chekhov failed to convince anyone to stage it and it was published in text form in 1928, translated into English in 1966, and first performed in London in a whittled-down Michael Frayn version in 1984.

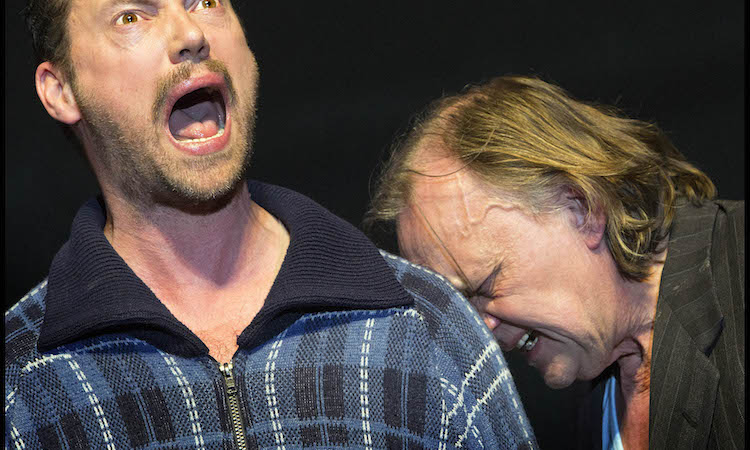

Our hero, Mikhail Platonov, is a cynical, irreverent, self-impoverished village schoolteacher with whom four women are in love. Relatively young in the original version, one of two radical changes in Perceval’s production sees Platonov (Bert Luppes) advanced to late-middle age; dishevelled and a bit grubby, he wears a torn t-shirt and ill-fitting trousers that at one point he pulls down then refastens badly, with his shirt poking out of the zipper. While earlier adaptations of the play portray him as a Don Juan type, this adaptation seeks to make Platonov as off-putting as possible, thus displacing our attention onto the other characters – most of who are worse!

A second major change (plot spoiler) is that this tragedy ends as it begins, with a suicide, rather than with the title character’s murder. Such a conclusion is defiant too of the tendency of Chekhov to ‘muffle’ such shocks by have them happen off stage or between acts, while the characters are prevaricating or the public taking a pee.

Death Becomes Them

Perceval’s 9-person & one-pianist production has been radically reduced in terms of character number, dialogue and action: yet the play still pays homage to Chekhovian themes, as well as recalling earlier versions of its performance history, both as stage production and in film.

All actors are on stage from the start, and there they remain: the four at the front almost immobile throughout; like Platonov’s memories revisited port-mortem, they gape into space, embalmed in an alluring yet impassive golden light.

“I am bored; deathly bored”, quips Anna – and she looks it. Anna Petrovna (Elsie de Brauw) is the educated widowed hostess of a garden party held annually to mark the end of winter, although the weather is already portentously hot. To Anna’s left, Platonov’s father-in-law Colonel Ivan Triletsky gradually drools into the nether. Just behind, the doctor Nicolai, Triletsky’s son, burps disgustingly, his speech often dissolving into a borscht of ticks and incoherent repetitions, a splurge of the rubbish that maddens all our brains and that we live in fear of one day slipping out. On the far right, Sergei Voynitzev completes the ghastly line-up with his little thrusting gestures and a hand that wanders down his pants. He, like the others, more than lives up to his dramatic purpose – that of putting Platonov as potential lover in perspective.

Anna Petrovna is just one of the ‘schoolteacher’s women’, the others are (as proper) Sasha, his wife; Sofya, an old flame, who turns up as Sergei’s unlikely fiancée, and, though less committal, Maria, a young chemistry student who stalks the back of the stage or hops along the train tracks that cut across it. It is along these rails that a grand piano moves, marking the time of the play and the remaining hour and a bit of Platonov’s life.

A Bunch of Flowers

One reason for seeing Platonov as a more complex character than a provincial Lothario, argues the British playwright David Hare in the introduction to his own adaptation of the play, is that that the women who fancy him take most of the action. This is a man “who things happen to”, reckons Hare, and who before impassioned pleas only responds, “to discover in love a purpose and a meaning which eludes him elsewhere”.

But if this is the case with P, then his quest is self-defeating and leaves him more isolated in the act of chasing love than of just getting on with it. This is also equally true of every one of the characters, for whom the blunt, dreary dialogue, not always intelligible, expresses the inadequacy of love in reality in comparison to the intangible allure of it as an ideal.

The piano is played by Jens Thomas, who intermittently accompanies the play with improvised singing that swerves from a melodramatic pop-rock, to the plucking and screeching sounds of some forms of contemporary jazz. With the piano’s progression, another character emerges from between the tracks with a bunch of flowers; it is the dashing and dastardly thief Osip, a startlingly good-looking man with a tendency to spit, who takes his place with this tragic team of grimacing gargoyles to wait for what is or what is not coming to them.

Platonov – Luk Perceval / NTGent

was @ Teatre Lliure / Grec Festival – Barcelona 2016

Photo credit: © Phile Deprez